In less than a decade, Kosovo held four parliamentary elections—all early calling—totaling at 23,202,194 euro. Of this amount, Central Commission of Kosovo spent 17,684,155, political parties 5,518,039 euro. Only for the 2019 election, the Commission allocated 5.7 million euro—regarded as the most expensive elections since Kosovo independence. Political parties meanwhile spent 2,111,285 euro—with LDK leading the list with 735,541, followed by VV—451,979, AAK—346,544, PDK—316,342, and Nisma—AKR 115,862 euro. Since 2001, Kosovo held 14 elections, national and local, which cost over 36 million euro, excluding expenses of political parties. The election and political party systems on the one hand, and political rivalries over the control of economic resources and organized crime on the other, account for the main factors for Kosovo’s short-lived governments. Political instability is one of the main features of fragile states, which Kosovo is still viewed as such, unfortunately.

Sebahate J. Shala

THERE’s an anecdote circulating in informal circles in Kosovo that says, if the country continues with the same trend, it will—sometime in the future—compete with Italy for the number of changing governments. Of course, the comparison is inadequate though the two countries share some commonalities. As parliamentary democracies, both have proportional election and multi-party systems—with Government as the main executive and the Parliament as representative body elected based on closed, respectively open lists of candidates.

In such contextualities, election and political party systems often force broad, unstable coalitions since no party takes enough votes as to govern alone. Consequently, government collapse, political instability, as well as shifting allegiances—based on party’s leaders or individual interests rather than ideological or programmatic orientations—are typical. Besides, Kosovo and Italy are widely known as corrupt countries ruled by politicians who use politics as a means to control organized crime and economic resources. Whereas Italy is one of the most corrupt countries in Eurozone, ranking 51 out of 180 countries in the 2019 Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index—in par with Malta, Saudi Arabia, and Grenada—Kosovo maintains its place as a highly corrupted country in the Balkans’ region ranked 101 of 180 countries. In addition to organized crime and corruption, a stagnating economy, political apathy, misogyny and discrimination of women as well as youth unemployment—attributed to Italy’s political instability—are common characteristics for Kosovo, too.

As of today, Italy holds the record for the number of short-lived governments, having changed 69 governments in 73 years, including the last one that took shape in August, 2019. Over the same period, Spain had 23 governments, France—13, United Kingdom—28, and Germany—26 governments. In three decades, Italy had 13 prime ministers while Germany had three chancellors, France—five presidents and United Kingdom—seven prime ministers. Silvio Berlusconi is the only premier to have served full-two-terms out of three mandates leading the country from 2001 to 2006 and 2008 to 2011. The average duration of Italian governments is less than 13 months per government—with a record broken from the Giuseppe Conte government—11 days short of its 15th month in power. This means that German Chancellor Angela Merkel—elected in 2005—have seen nine Italian prime ministers come and go while she has retained the power.

Kosovo: 4 Governments in Less Than 10 Years=Millions Spent

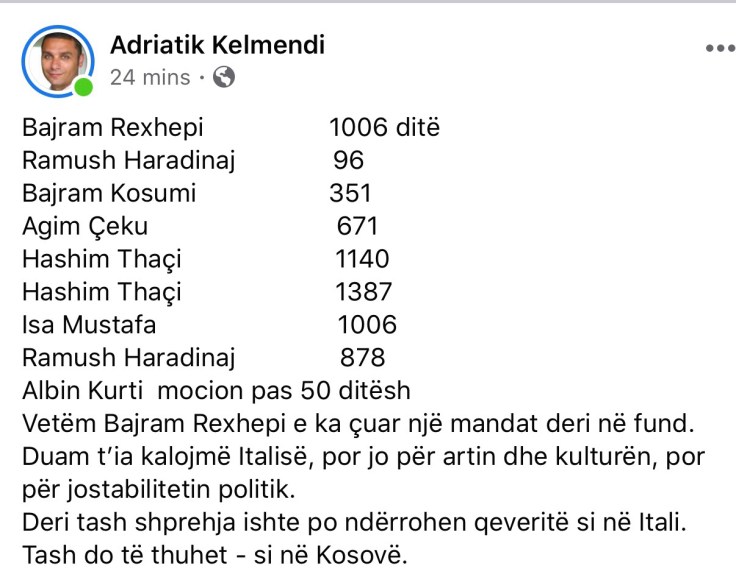

THE small-size, young Kosovo has–in less than 10 years and almost 13 years as independent state—changed four governments, respectively five, with an average duration ranging from less than three to two years to only 51 days. So far, no government and primer served a full-term mandate except for the first Prime Minister Bajram Rexhepi of Democratic Party of Kosovo (PDK) who led a government of broad coalition through March 2002 to December 2004. The subsequent government composed of Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK), Allegiance for Future of Kosovo (AAK) and minorities lasted more than two years—a period that had seen three different prime ministers coming from AAK, Ramush Haradinaj, Bajram Kosumi, and Agim Ceku.

In the period between 2007 and 2017, PDK won four elections—not the majority though—necessary to form the government on its own. All those elections were early calling with governments serving in an average less and no more than three years out of four-years mandate. All but the last one, Haradinaj Government, were toppled with the initiative of PDK—whose partners varied from LDK, AKR and minorities (Thaci Government I, 2008—2010) to AKR and minorities (Thaci Government II, 2011—2014), to LDK and minorities (Mustafa Government, 2014—2017), to AAK, AKR, Nisma, and minorities (Haradinaj Government, 2017—2019). The Kurti Government, composed of VV, LDK and minorities, lasted only 51 days. It toppled following a no-confidence vote initiated by LDK—the partner of coalition—in part due to internal disagreements regarding the lift of tariffs against Serbia—pressured by the U.S. in order to resume dialogue between Kosovo and Serbia on Kosovo final status settlement, including the emerging conflict on competences between Prime Minister and President in leading the dialogue with Serbia and in managing the crisis as a result of Coronavirus COVID-19.

Figure 1.1. Adriatik Kelmendi, Facebook, March 25, 2020.

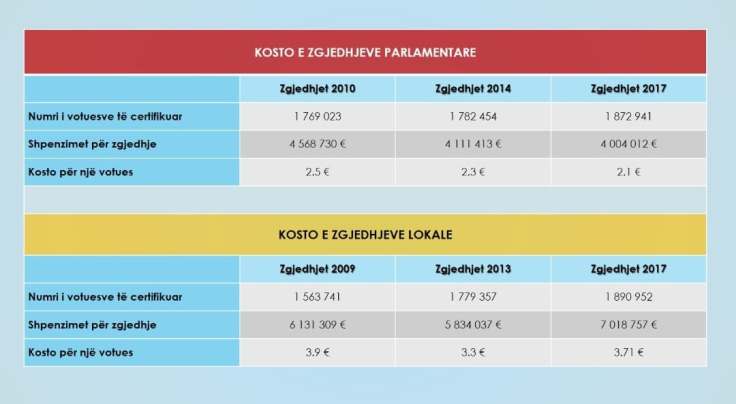

Since 2001, Kosovo held 14 elections, local and national (15 adding the upcoming election to be held on February 14, 2021), which cost the country over 31 million euro based on Kosovo Central Commission (KCC) data, excluding last election held on October 6, 2019. Adding 5.7 million euro allocated to 2019 election—considered as the most expensive parliamentary elections since independence—and let’s suppose that the KCC spent 5 million of that amount, the total cost of 14 election cycles in Kosovo goes to over 36 million euro. Only in three elections, 2010, 2014, and 2017, Kosovo spent 12,684,155 euro plus 5 million of 2019-election, that means 17,684,155. As the table 1.1. indicates, the 2010- election was the most expensive one compared to 2014 and 2017 elections (excluding 2019 election)—totaling at 4,568,730 euro—and considering here the re-voting process in Mitrovica and Skenderaj.

Table 1.1. Cost of Parliamentary Elections in Kosovo, 2010, 2014, and 2017. Source: Kosovo Central Commission.

Table 1.1. Cost of Parliamentary Elections in Kosovo, 2010, 2014, and 2017. Source: Kosovo Central Commission.

Political parties on the other hand spent 5,518,039 euro in four last elections. Only in the last election, 25 political parties, according to KCC, spent 2,111,285 euro: 1,966,269 were spent by major parties, VV, LDK, PDK, AAK, Nisma and AKR. This is far more than the 2017 election which cost political parties (17) 777,625 euro in total—excluding AAK and AKR—which didn’t submit the auditing report; the main political parties spent 644,365 euro. 975,442 were spent by 23 parties in 2014 election (excluding AKR). 1,631,435 euro were spent by 29 parties in 2010 election—including LDD and re-voting in Mitrovica and Skenderaj—while excluding three parties belonging to the minorities. Of the money spent in 2019 election, LDK leads with 735,541 euro, followed by VV—451,979, AAK—346,544, PDK—316,342, and Nisma—AKR 115,862 euro.

| Political Parties | 2010 | 2014 | 2017 | 2019 | Total |

| PDK | 418,363 | 307,577 | 329,125 | 316,342 | 1,317,409 |

| LDK | 297,713 | 182,283 | 209,624 | 735,541 | 1,425,161 |

| LVV | 102,560 | 91,724 | 146,225 | 451,979 | 792,488 |

| AAK | 176,705 | 291,750 | 346,544 | 814,999 | |

| AKR | 461,309 | 115,862 | 577,171 | ||

| Nisma | 14,712 | 14,884 | 29,596 | ||

| Others | 174,785 | 109,648 | 133,260 | 145,016 | 562,709 |

| Total | 1,631,435 | 997,694 | 777,625 | 2,111,285 | 5,518,039 |

Table 2.2. Political Parties Expenses in Elections 2010, 2014, 2017 and 2019. Source: Kosovo Central Commission.

Why do Italy and Kosovo Governments Collapse so Often? Electoral and Political Party Systems

THE collapse of Italy’s governments is attributed to the electoral and political party systems. Italy has a proportional (closed-list) voting system, which guarantees a big majority to the winning party in the parliament if the party wins at least 40% of the general vote. If this vote is not attained, then a coalition of forces is necessary. The Italy’s multi-party system imposes a coalition formula as none of the parties can form the government alone. Kosovo, too, suffers from the same problem. Kosovo is a single, multi-member electoral unit with a proportional representation voting system which shifted from closed to open-list in 2007: 100 of 120 seats are elected proportionally while 20 seats are reserved for national and ethnic minorities. The election threshold for a party, coalition and/or independent candidates is 5% of general vote.

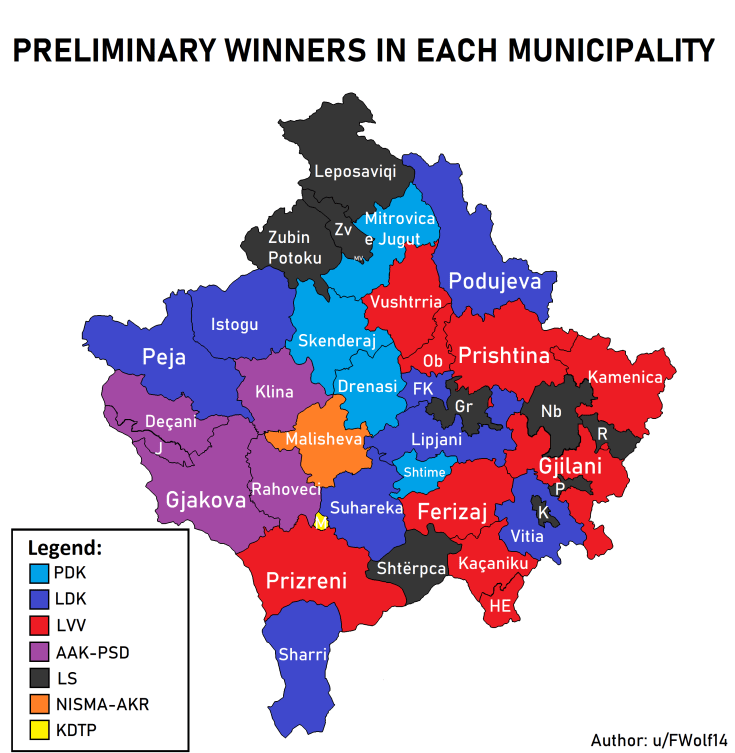

Figure 2.2. The Election Map in 2019 Parliamentary Election in Kosovo.

Kosovo transitioned from one-party to the multi-party system and pluralism following the liberation from Serbia in 1999. The election system meanwhile was designed with the intention to enable a broader representation and inclusiveness in the society based on social, ethnic and gender representation. Apparently, the proportional election system is not working and—in spite—of ongoing efforts since 2011, the electoral reform has stagnated. There is no general consensus among political spectrum to find a model that would best fit Kosovo’s context. In a multi-party system such as in Kosovo with about 30 parties running in national election, no party is strong enough as to form the government; therefore, coalitions are necessary (KIPRED, 2015). However favorable it might be, the system in Kosovo, as Mentor Agani argues, often creates obstacles for the functioning of democracy by generating political crisis such as the one in 2014, as no party alone can create the government. In seven parliamentary elections since 2001, no single party—except LDK that initially won a high percentage of vote—won the majority required to form the government. When Kosovo faced a six-month political crisis following the election in 2014, the voter turnout, as Gent Gjikolli suggests, was 43% resulting of 30 running political parties and initiatives while PDK together with other parties won the election with 30% of the total vote (Id.).

In most of the cases, coalitions are result of interests of parties’ leaders or individuals rather than based on ideological or programmatic orientations. As Albert Krasniqi concludes: “The fact that Kosovo’s political scene is such that the rise of new parties is extremely difficult without coalitions with the old parties, further hinders the change of the existing situation for better—the need for new parties to connect with old coalitions obliges the new parties ‘to respect the rules of the game,’ i.e. to adopt undemocratic practices.” (Id.)

Kosovo—A Fragile State

THOSE who strongly oppose Kosovo’s statehood, namely Serbia and its allies, would like to see the young country fail. Often, they refer to Kosovo as a failed state due to political instability that the country has faced following its independence in 2008, especially since 2010 election—marked with massive vote theft and manipulation of election result from PDK. If political parties do not agree for a solution and if the COVID-19 crisis allows, Kosovo would soon go in another cycle of election sometime this year or next.

Political instability—which Kosovo has been going through for a decade now—is one of the main features of failed states. But Kosovo is not a failed state. Failed states, as Global Policy defines, are those which can no longer perform basic functions such as education, security, or governance, usually due to fractious violence or extreme poverty. Kosovo has never reached that point. The country is in a fragile state although it’s not included in the Fund for Peace’s fragile states’ assessment list. There are many definitions of fragile states. According to International Monetary Fund (IMF), fragile states are those whose poor quality of policies, institutions and governance, substantially impairs economic performance, the delivery of basic social services and the efficacy of donor assistance. Some of the characteristics attributed to them include weak governance, limited administrative capacity, chronic humanitarian crises, persistent social tensions, and often, violence or the legacy of armed conflict and civil war.

Fragility, as the EU frames, refers to the weak or failing structures and situations where social contract is broken due to state’s incapacity or unwillingness to deal with its basic functions: service delivery, management of resources, rule of law, equitable access to power, security and safety of the populace and protection and promotion of citizens’ rights and freedoms. In measuring the vulnerability of state to collapse or their vulnerability in pre-conflict, active conflict and post-conflict situations, Fund for Peace through Fragile States Index uses 12 conflict risk criteria summarized in four indicators to determine whether conditions are improving or worsening: cohesion, economic, political, and social. In the first one—factionalized elites and group grievances are highlighted, in the second—uneven economic development, and in the third—state legitimacy and capacity, public services and rule of law.

The World Bank evaluates state fragility through the Country Policy and Institutional Assessment (CPIA), which uses 16 criteria grouped in four clusters: economic management, structural policies, policies for social inclusion and equity, and public sector management and institutions. Based on the organization’s Risk and Resilience Assessment, Kosovo in recent years has been largely stable, retaining a degree of fragility and potential for violence. The World Bank identifies three main fragility risks: economic and political disenfranchisement, especially of youth; the unresolved issues with Serbia and interethnic relations; and the motives and actions of various political actors capitalizing on structural drivers of fragility.

Factionalized elites and group grievances, uneven economic development and resource distribution, questions of legitimacy and capacity, as well as rule of law—are found in Kosovo additionally to lack of a national unity and social cohesion. Kosovo, as Carleton University suggests, is experiencing a legitimacy and capacity issue in its state of affairs due to systemic isomorphic mimicry: the country is trapped in a feedback loop, fostering ineffective governance, decreasing international recognition, and weak service delivery from its institutions.

“The primary fragility drivers are governance and economy, whereas the secondary fragility drivers are security and crime, human development, demography, and environment. The primary fragility drivers contribute to three main risks that are weakening its state capacity and legitimacy: informal economy, the rule of law, and service delivery. In addition to its issues with international recognition, Kosovo’s internal performance has been mostly stagnant across all indicators, but a recent change in the government has seen a decrease in its governance and political stability with the rise of PM Albin Kurti.” (Carleton University, Ottawa, January 6, 2020)

International watchdogs emphasize weak rule of law as one of the major issues that has hampered the democratic and judiciary functioning, governance, as well as economic development in the country (EU Commission, 2019).

Leave a comment