The choice between a European army or a strengthened EU pillar within NATO has been a key dilemma for European leaders over the past decade. The decision is central to shaping the EU’s strategic autonomy as it defines the bloc’s reliance on the U.S. through NATO versus its capacity for independent defense. While scholars offer varying perspectives, a stronger EU pillar within NATO is increasingly viewed as the more politically and practically feasible path.

Sebahate J. Shala

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 sent shockwaves across Europe, reviving urgent questions about the continent’s defense capabilities and strategic autonomy. For decades, European security has relied heavily on the transatlantic alliance—with the United States (U.S.) acting as both guarantor and leader within NATO. However, this historic transatlantic relationship is under serious strain. Washington’s increasing pivot toward the Indo-Pacific combined with domestic signals that U.S. security commitments to Europe may no longer be unconditional, have forced European leaders to reconsider their long-standing dependence. Calls for a more autonomous European defense posture are not new. Since the failed attempt to establish a European Defense Community (EDC) in 1954, the idea of a unified European defense has repeatedly surfaced—often in times of geopolitical stress. Yet despite numerous initiatives, treaties, and frameworks, the European Union (EU) continues to face deep internal divisions, limited military interoperability, and persistent reliance on American capabilities, particularly in intelligence, logistics and nuclear deterrence.

The war in Ukraine has underscored Europe’s strategic vulnerabilities while opening a window for renewed defense integration. Many argue that Europe should deepen defense integration and take greater responsibility for its own security, reducing reliance on the U.S. But critical questions remain: Can EU realistically fill the gap left by a receding U.S.? Does it possess the political unity, industrial base, and operational capacity to build a truly autonomous European army? Or is the concept of strategic autonomy an ideal out of reach without threatening or undermining NATO itself? This article seeks to answer these questions. Currently, the EU faces three broad options: integration, cooperation, or starting over. Proponents argue that strategic autonomy reduces dependence on the U.S., enhances the bloc’s economic and geopolitical influence, and enables Europe to assert itself as a collective military power while positively contributing to the transatlantic relationship. Critics, however, highlight political and practical obstacles, arguing that ambitions for a fully autonomous European defense are limited. Instead, they advocate for deeper European defense cooperation under existing programs, alongside the creation of a stronger EU pillar within NATO—an approach that could advance Europe’s defense and global interests.

This article explores these questions through a four-part analysis. The first section reviews the historical development of European defense cooperation from the early postwar period to the present, highlighting the major turning points and obstacles. The second section assesses the current EU capabilities, particularly in the light of ongoing war in Ukraine. The third section presents competing arguments regarding the feasibility of EU strategic autonomy on defense. Finally, the paper considers potential future scenarios for EU security, including the prospects for a European army and the evolving relationship with NATO.

Historical Background: Europe’s Long Road to Strategic Autonomy

Strategic autonomy has become a centerpiece of European leaders’ discussions since 2016 when Global Strategy for Foreign Policy and Security (EUGS) introduced the notion in reference to the EU’s developing capacity for autonomous action to “deter, respond to, and protect ourselves against external threats.” (2016) The debate—including the creation of an autonomous European army—has intensified in subsequent to Russia’s military aggression in Ukraine combined with increasing U.S. unpredictability regarding security guarantees and the shifting American focus to Asia and Indo-Pacific. The Europe’s pursuit of an integrated defense system is not novel. The idea dates back to the early 1950s when European countries, supported by the U.S., sought to institutionalize their military cooperation through the proposed European Defense Community (EDC), a supranational defensive organization envisaged to integrate the national militaries into a single European defense structure (European Defense Community Treaty, 1952). The EDC was designed to defend its members against military aggression in response to pressures stemming from Soviet expansionism and German rearmament in the wake of the World War II. The project however collapsed following the French National Parliament’s rejection, revealing deep national political divisions over national sovereignty and integration on defense matters (Lorenzo Fedrigo, Geopolitical Monitor, April 23, 2025).[i] Alternatively, Europeans settled for NATO on collective defense—with the U.S. as the leader and primary guarantor of Europe’s security and defense under the Atlantic Alliance umbrella. Therein, the need for a deeper integration became secondary to transatlantic security arrangements. Meanwhile, the issue of German rearmament was addressed through the Western European Union (WEU), with West Germany joining this military association in 1954 and NATO in 1955 (Id.). Established under the amended 1948-Brussels Treaty, the WEU served as the principal forum for coordination of matters on security, defense, and armament cooperation between European countries (University of Pittsburg, Archive of European Integration), it helped build the European Security and Defense Identity (ESDI) within NATO (Washington Summit, NATO, April 23, 1999) and was instrumental in developing the European security and defense policy in the 1990s (Oxford Research Encyclopedias, 29 July 2019).

Strategic autonomy reemerged in the 1990s, but in the absence of major threats, progress toward deeper defense integration remained limited, whilst defense initiatives—intergovernmental. “The concept lost favor due the U.S. opposition and commitment to NATO.” (Bergmann, 2025) The Maastricht Treaty (1992) marked a turning point in that it set up the European Union and formalized the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), laying out the groundwork for future security and defense infrastructure, including standing up a European army (Fatih Ceylan, European Army, Is It a Cursed Project, Foreign Analysis, August 15, 2023). The defense policy was incorporated in the CFSP until the defense policy branch came into being in 1999—becoming an integral part of the CFSP (Lefebvre, 2024). The Franco-British Summit, producing the St. Malo Declaration (1998), was pivotal in establishing the EU as a defense player, recognizing the need for an “autonomous capacity for action, backed up by credible military forces” in case when NATO is unwilling or unable to act (Id.). At the St. Malo, the heads of the United Kingdom (UK) and France, Blair and Chirac, proposed a 60,000 rapid reaction force to respond in international crisis, reassuring transatlantic partners that NATO would retain the bedrock of the EU’s national security and defense, and that every action would be taken in consultation with Atlantic Alliance and other partners (Richard Norton-Taylor & Michael White, The Guardian, November 26, 1999). The St. Malo Declaration used the WEU assets as a reference point to uphold the principle of no-decoupling from NATO, thereby avoiding unnecessary duplications in defense structures. The Berlin Plus Agreement 2003 draw upon such conclusions, accordingly, EU launched a separate but not inseparable defense dimension pursuant to the-1999 NATO Washington Summit formulation, reaffirming the EU-NATO existence in a modus vivendi (Id., Ceylan, 2023). Responding to the tragedy of the Balkans’ wars and the EU’s inability to act without U.S. assistance, the Franco-British Summit made a breakthrough in breaking the UK’s resistance over the EU defense integration and the country’s reliance on NATO (Id., The Guardian, November 26, 1999), and officially embarked the European Security and Defense Policy (ESDP).

Building on the momentum of the St. Malo, the early 2000s saw the birth of the ESDP framework leading to several key defense mechanisms, the European Defense Agency (EDA), the European Union Military Staff (EUMS), and the onset of the Battlegroups—a multinational, military units’ concept—designed for rapid deployment in crisis and conflicts around the globe. In line with Berlin Plus arrangements, EU launched the first peacekeeping missions—from Africa to Middle East to the Balkans—accounting for more than 30 operations since 2003 onwards, with 22 still ongoing (Lefebvre, 2024). The Berlin Plus defined the scope of cooperation and complementary relationship between the EU and NATO, based on strategic partnership and effective mutual consultation. It also reassured the EU access to NATO’s assets and planning capabilities for EU-led military operations, culminating in the NATO-EU Declaration on ESDP in 2002 (Rittimann, 2021). Yet, in the realm of ESDP, the decade passed without major achievements—except for the adoption of the European Security Strategy in 2003 and the Lisbon Treaty in 2009—both influenced by series of events, including the Iraq War, Russia-Georgia dispute, financial crisis, and the failure of the European Constitution. Regarded as the cornerstone in the development of the ESDP (EU External Action, March 28, 2022), the Lisbon Treaty added relatively little new, but it renamed the ESDP as the CSDP and incorporated the collective defense clause—Articles 42.7 and 222—to be invoked by EU members in the event of an armed or terrorist attack against them (Graf von Kielmansegg, The Historical Development of EU Defense Policy: Lessons for the Future? VerfBlog, March 25, 2019). The treaty, too, created positions of the President of the European Council and the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs, as well as expanded powers of the European Parliament, putting it on an equal footing with the Council of Ministers (European Parliament).

The CSDP gained political momentum from 2014 in response to geopolitical reconfigurations and external shocks (Crimea, Brexit, and Trump comments on NATO), resulting in numerous strategies and initiatives—that increased in number after 2016 (Rutigliano in Beaucillon et al., 2023: 767). The EU Global Strategy (EUGS), the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), and the European Defense Fund (EDF) were subsequently established. The EUGS represented a “paradigm shift” (Id: 766) as it incepted the strategic autonomy concept, nurturing European ambitions for autonomous action “if and when necessary” and in cooperation with partners “wherever possible,” while also reaffirming the bloc’s commitments to a rules-based global order grounded in multilateralism and collective defense (2016: 19). The strategy involves three main pillars: new political goals—seeking a strategic autonomy and greater responsibility for Europe’s own security and as a security provider in the global scene; new financial tools needed to develop defense capabilities; and a set of concrete actions as a follow-up to the EU-NATO Joint Declaration, identifying areas of mutual cooperation (EU External Action, March 28, 2022). The PESCO aimed at expanding areas of mutual cooperation for joint development of defense capabilities, encouraging greater integration amongst member states on armament development (Rutigliano in Beaucillon et al., 2023: 767-769). The initiative aligns national defense planning, promotes collaboration and reinforces European defense capacity by pooling and sharing resources necessitated to develop armaments in a synergetic and cooperative manner, whereas respecting the full national sovereignty over military capabilities (Id: 770). Once joined, members are required to fulfill 20 binding commitments to harmonize national defenses and strengthening cooperation, and also provide annual assessments on methods they will use to achieve specific objectives—evaluations to be reviewed by PESCO Secretariat (Id., 770). Founded in 2021, the EDF, a Commission-based instrument, meanwhile, seeks to foster competitiveness and innovation in European industry and research policy through supporting cross-country collaborations on security and defense matters (Kilic, 2024: 61). The EDF encompasses both research and capability development dimensions. It is designed to link defense priorities with capabilities—not only to provide financial support to the defense industry, but also to ensure security of supply and contribute to the Union’s development of strategic autonomy (Id: 60).

The Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 triggered a renewed need for cooperation whilst growing the political consensus amongst the EU members—especially in France and Germany—about a greater European strategic autonomy. Once a peripheral notion, strategic autonomy became a central theme of the EU leaders’ discourse (Id., Ceylan, August 15, 2023). Consequently, EU introduced the European Political Community (EPC), the Strategic Compass, the Coordinated Annual Review on Defense (CARD), and the renewed EDA. The Strategic Compass presents a wider perspective of strategic autonomy, including on defense (Id.), and although unveiled in the aftermath of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, it addresses a whole range of global threats not solely to the war in Ukraine (EU, 2022). The strategy sets out a desirous plan focused on strengthening the EU security and defense policy by 2030 through reinforcement of civilian and military missions by developing a 5000-deployment readiness, increase of defense expenditures and investments in capability development by reducing technological and industrial dependencies, enhancement of strategic partnerships with NATO and other global organizations, and development of a Security and Defense Partnership Forum (Id: 11). In this respect, the-2023 EDIRPA, a Commission-proposed regulation, is seen as one of the most ambitious steps to date (Kilic, 2024: 62). The regulation, same as CARD 2024, highlights the EU most urgent capability needs and incentivizes member states to procure defense products in a joint, cooperative manner (Id.). Further, the CARD seeks to align and synchronize national defense planning and investment across the bloc (Rutigliano in Beaucillon et al., 2023: 767), emphasizing the need “for collaborative initiatives to address critical military capability gaps and prepare for high-intensity warfare.” (EU External Action, November 19, 2024) Nonetheless, these mechanisms, namely the Revised Capability Development Plan (CDP), CARD, PESCO, and to some extent, the EDF—designed to boost the EU’s operational capabilities—fail to achieve the promise: expanding and strengthening the European strategic autonomy (Kilic, 2024: 63). As Paul Taylor put it, “Member states may have signed up to an EU Strategic Compass and pledged in their 2024-2029 Strategic Agenda to ‘invest more and better together, reduce our strategic dependencies, scale up our capabilities and strengthen the European Defense Technological and Industrial Base.’ But that is not the course they are on.” (2024)

Legal Constraints on the Operational Domain: CSDP Not Designed to Defend Europe

Certainly, Russia’s confrontation with the West over Ukraine has mobilized forces within EU in pursuit of a deeper defense integration; however, it was the U.S. uncertainty regarding security assurances for Europe, following Trump’s reelection, coupled with President’s repeated threats to withdraw from NATO and exit Ukraine, and the U.S. pivot toward the Indo-Pacific—that fundamentally changed Europe’s course of action. At the Munich Security Conference, held in February 2025, the U.S. signaled its disengagement from European affairs—an act that prompted EU leaders from Warsaw to Berlin—to review their defense doctrines and rally member states, including the UK, around what was described as once-in-a-generation-moment. The EU Commission unveiled the White Paper ReArm Europe Readiness 2030, a colossal defense plan, outlining the rationale for rearmament while calling for a once-in-a-generation-surge in European defense investment (EU Commission, 2025). “The moment has come for Europe to re-arm. To develop the necessary capabilities and military readiness to credibly deter armed aggression and secure our own future, a massive increase in European defense spending is needed.” The ReArm Europe defines Russia as a “fundamental threat to Europe’s security,” it mentions China’s erosion of strategic balance in Indo-Pacific as the contributing factor to the deteriorating security environment, and highlights the broken relationship with U.S. as driver for Europe’s comprehensive defense plan of action (Maslanka, 2025). The strategy identifies seven priority capability areas for investment: air and missile defense, artillery, ammunition, drones and counter-drone systems, infrastructure supporting military mobility, artificial intelligence and electronic warfare, and strategic enablers (Bissacio, March 27, 2025). It sets forth paths on defense capability reinforcement, addresses critical capabilities’ shortfalls and dependencies on U.S., calls for the increase of military and financial assistance for Ukraine, and the development of military readiness to deter armed aggression (Id.). The ReArm 2030 urges member states to develop an integrated defense market system by simplifying regulations and expediting joint procurement procedures, collaborating and purchasing from European manufacturers, and approving a package of defense policies and legislative proposals, involving the plan to rearm (EU Commission, 2025). To this end, the Commission proposed a financial support package—a key component of the White Paper—which seeks to mobilize over $841b alongside $169b pledged through the SAFE instrument (Security Action for Europe) for joint borrowing—necessitated for development of military capabilities (Maslanka, 2025).

The above-mentioned strategies and initiatives constitute an integral part of a comprehensive defense package in furtherance of the CSDP architecture as they are complementary and mutually reinforcing tools (Rutigliano in Beaucillon et al., 2023: 767). They, too, intend to bolster the European defense and contribute to the development of strategic autonomy (Kilic, 2004: 64). Nevertheless, these initiatives—PESCO being the central one—do not address the CSDP’s operational dimension, namely the conduct of military operations; rather, they focus on the capability area, addressing the capability shortcomings, defense planning and building efficient force structures (Graf von Kielmansegg, 2019). Despite strategic needs, the operational aspirations could not be fully materialized—primarily in the absence of a consensus-based decision-making in the CFSP and CSDP—and because of the opposition over the substance and the degree of strategic autonomy (Kilic, 2024: 54). As opposed to defense industrial supranational scope, the defense capability planning and development projects are designed as intergovernmental mechanisms. The CSDP, for instance, is strictly intergovernmental compared to the EDF—regarded as a supranational instrument and a game-changer respective to EU development of strategic autonomy (Id: 64). The CSDP consists of two dimensions: the operational, which is responsible for conducting EU military operations and establishing necessary institutional structures, and the capability one, which develops military capacities through coordinated armaments policy and defense planning mechanisms (Graf von Kielmansegg, 2019). The operational dimension of CSDP remains central to European defense: first, as a natural extension of a more unified and assertive European foreign policy in managing international relations; and second, because the post-Cold War geopolitical context underscored the need for the Union to develop the capacity to manage international crises (Lefebvre, 2024: 2).

The EU, in essence, as its leaders claim, is a peace project, an exclusively civilian, soft power—conceived as a politico-economic rather than a defense community (EUGS, 2016). Founded as a civilian and democracy-support oriented project, EU has gradually shifted toward a civil or civil-military enterprise (Lefebvre, 2024: 2), moving away from democracy-support to a more narrowly defined, pragmatic security cooperation (Farinha, 2025). Accordingly, the organization has expanded its role as a global security provider, deploying over 30 peacekeeping missions—with tasks ranging from humanitarian and rescue to conflict prevention and peace-keeping to combat forces in crisis management (Bilquin & Chahri, 2024). The civil-military integration, according to Lefebvre, has been crucial to CSDP work, and though theoretically the Union could conduct combat force operations for crisis management, in reality, it doesn’t (2024: 3). Legally, as Graf von Kielmansegg argues, the CSDP is limited to small military missions—not for collective self-defense against a direct armed attack, whereas the collective defense clause—albeit expanded the CSDP scope—in practice, it doesn’t provide EU with a military role. In other words, the CSDP does not guarantee the defense of Europe (Id: 2019). Herein, the extremely rapid progress in development of politico-military structures, Graf von Kielmansegg continues, does not radically change the CDSP reach and the possibility of an EU force replacing NATO because of the national sovereignty and the principle of no-delinking upon which the CSDP was built (Id.). NATO, as EU treaties enshrined, preserves the exclusive authority on collective defense—a principle reiterated in the Strategic Compass, most recently. Therefore, the collective defense article attached to European treaties (Article 42-7 TEU from the 1948-Brussels Treaty) only reinforces NATO preeminence on collective defense (Lefebvre, 2024: 5). As Meijer and Klein put it, “The institutional framework for military operations in articles 42-46 TEU focuses primarily on crisis management missions outside the EU, aimed at stabilization and capacity-building. Examples include EUNAVFOR […].” (Meijer & Arjen, VerfBlog, March 6, 2025).

Current Capabilities and Strategic Gaps: EU Strategic Dependency on U.S. Persists

Donald Tusk, Prime Minister of Poland: “Europe as a whole is truly capable of winning any military, financial, economic confrontation with Russia, for it is simply stronger.” Al Jazeera, March 6, 2025.

The European Union has responded to war in Ukraine with an unprecedented surge in defense spending and political rhetoric on the need for a greater strategic autonomy. On the state level, governments reassessed defense capabilities, raised military budgets and expenditures, modernized military equipment, committed to joint procurement projects, and pledged to reinvigorate ammunition production. Germany, for example, long criticized for underinvestment on defense, launched the 2022-Berlin’s €100B Zeitenwende program to revamp its chronically underfinanced and underequipped military, the Bundeswehr, and help the country to finally reach the NATO’s 2 percent threshold on defense spending (Lauren Gehrke & Hans Von Der Burchard, Politico, May 30, 2022). Yet, Europe faces many challenges—from underspending on military to dependency on U.S. critical capabilities to undersized manufacturer and non-collaborative procurement—issues that will be discussed in this section.

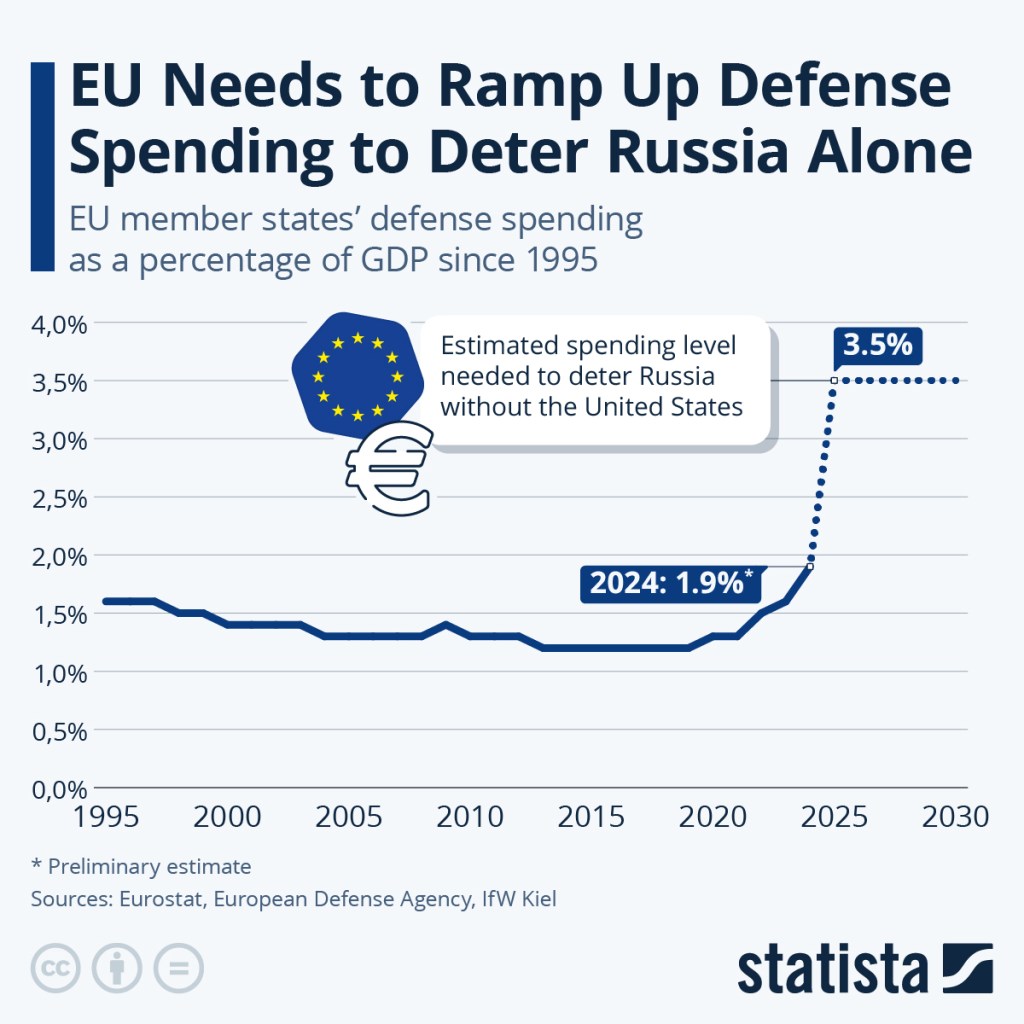

First and foremost, the EU defense budget, despite increases in the past few years, remains low comparable to U.S., and is projected to be surpassed by Russia’s, soon. Europe’s current state of defense funding is, in fact, a consequence of decades of underspending due to budget reductions after the end of the Cold War and following the financial crisis in 2008-2009. If defense spending had maintained the pre-2008 levels, EU, as Scazzieri indicates, would have spent (approximately) an additional $189b (€160b) by 2018, and if all members had spent 2 percent on defense as required by NATO, that would have resulted in (approximately) an additional $1.3 trillion (€1.1 trillion) between 2006 and 2020 (2025). The EU’s gap in military spending remains significant compared to other global powers. For example, through 2000-2020 (in constant 2022 dollars), Russia’s defense spending increased by 360 percent, China’s—by 596 percent, and the U.S.— which remained the highest in the world—by 60 percent. In sharp contrast with these quasi-global trends, Europe’s military expenditures either declined or remained largely stable over the same period (Grand, 2024: 8). It was Russia’s act of aggression against Ukraine that forced the EU countries to increase their military budgets and spending. Across the continent, member states raised defense expenditures by 50 percent, spending, based on NATO estimates for 2024, $169b more per year compared to 2014 (Id: 6). In 2024, the EU combined military expenditures reached $457b—11.7 percent higher than in 2023 (Lucia Mackenzie, Politico, February 12, 2025). Although military spending has grown by 30 percent since 2021, the EU collective defense spending accounted for only 1.9 percent of economic output in 2024 (Derek Bissacio, Defense and Security Monitor, March 27, 2025). The EU defense expenditure still remains low compared to the U.S. given its military constellation: the bloc spends three times less than U.S. and has six times as many armaments programs (Lefebvre, 2024: 3). Russia’s defense spending, on the other side, has surged since the outbreak of war in Ukraine, exceeding, as Mackenzie reported, the combined military expenditures of all European countries (Id.). Only in 2024, Russia spent $145.9b, or 6.7 percent of GDP—over 40 percent more than the previous year. And, while some NATO European members still fall short of the 2 percent GDP benchmark, Russia’s defense budget has remained above 6 percent for several years, having ranged between 3-4 percent annually for a decade prior to the Ukraine’s invasion (Bissacio, 2025). To close this gap, Europe would need to allocate roughly 3 percent of GDP to defense sector yearly (Scazzieri, 2025), a similar amount (3 to 3.5 percent of GDP) that French President, Macron, urged his European counterparts to agree with (Clea Caulcutt and Laura Kayali, Politico, March 3, 2025).

Second, one of Europe’s major challenges is its strategic dependence on U.S. and the Union’s weakened defense readiness, resulting from decades of underinvestment. European defense remains in a fragile state; much of its military hardware was described as being in a “shocking state of despair.” (Bergmann et al., 2021). Although the situation has evolved, one fact remains clear: EU continues to rely heavily on U.S. assets for its security and defense—a dependence that has intensified since the onset of the war in Ukraine (Scazzieri, 2025). Unfortunately, the Union, as Scazzieri argues, has compromised its investment priorities, focusing on expeditionary operations whilst neglecting equipment, stockpiles, and readiness efforts needed for high-intensity conflict—with the possibility to never acquiring important military capabilities (Id).

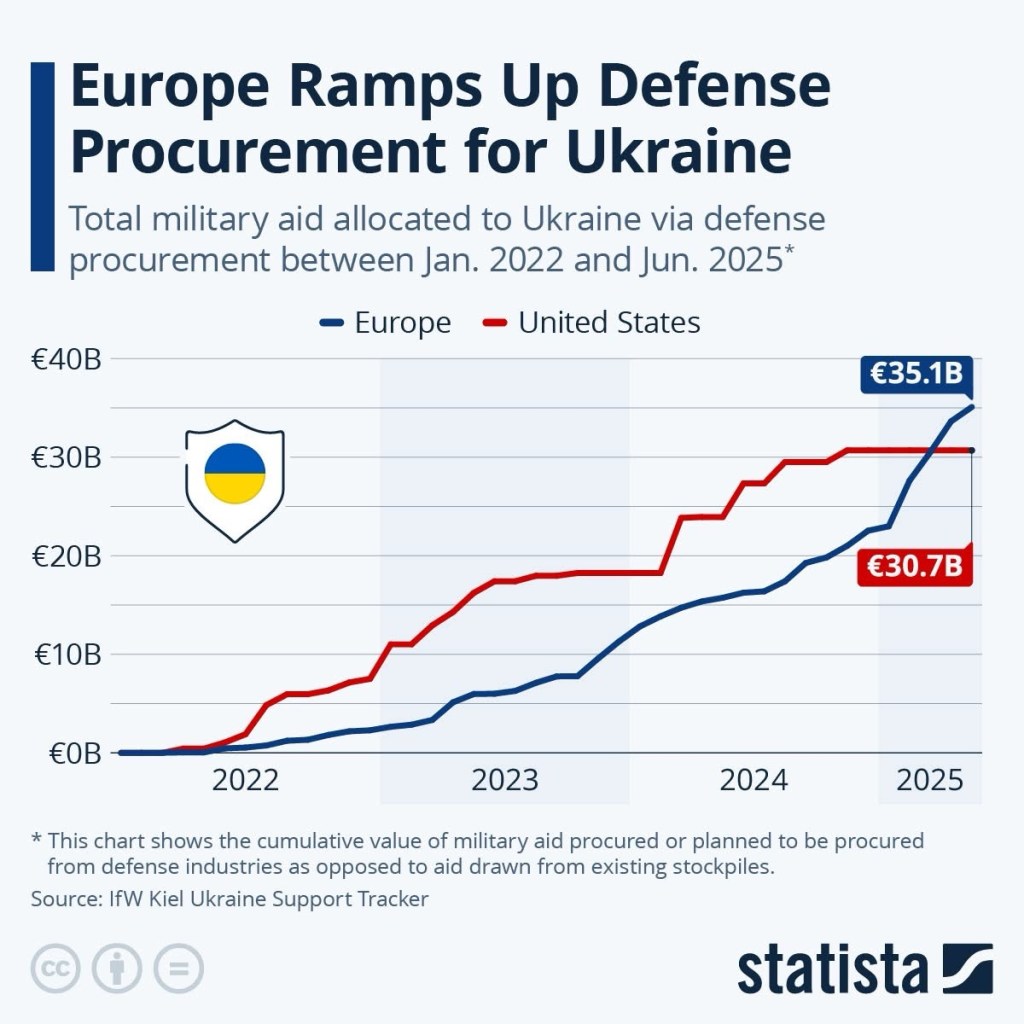

America is the backbone of European defense architecture through NATO, providing the most advanced technologies, extensive arsenals and significant military expertise, whilst supporting Ukraine—from key real-time intelligence to satellite reconnaissance to logistics. Currently, the U.S., as Sinead Baker and Thibault Spirlet of Bussiness Insider reported, consists 20 percent of total military hardware in Ukraine, delivering the most powerful weaponry—Javelin anti-tank missiles, F-16 fighter jets, Patriot interceptor missiles, and the HIMARS rocket launchers—hard to be replaced by Europe (March 5, 2025). Though the joint Ukraine and Europe’s produced ammunition comprises the remaining 80 percent (55 percent+25 percent), the-20 percent American ammunition, according to Business Insider, is “the most lethal and important” one (Id.). In total, U.S., as Brady et al. illustrate, committed $66.5b in military assistance and over $50b in financial aid in support of Ukraine’s war efforts (2025). While substantial, these amounts remain smaller than the EU’s contributions, which total nearly $200b: $162b in financial, military and humanitarian/refugee aid in addition to $54b pledged to Ukraine Facility for recovery, reconstruction and modernization (EEAS, June 16, 2025). However significant and growing, the European support and Ukraine’s own defense industry combined, as Brady et al. argue, cannot fully replace the U.S. capabilities in case of an American retreat from Europe and Ukraine. It depends, though, to the extent the U.S. support is cut off and on Europe’s ability to fill the capability loophole left by an eventual American withdrawal (Id). As Richter’s findings indicate, the EU would need to allocate only an additional 0.12 percent of its GDP annually to replace U.S. military contributions to Ukraine. Permanently protecting Ukraine and deterring Russia, however, would require substantially higher financial commitments—over $270 (€250b) in additional annual military spending—raising the Union’s combined defense expenditure from just under 2 percent of GDP to approximately 3.5 percent per year (2025).

Sources: Felix Richter, “EU Needs to Ram Up Defense Spending to Deter Russia Alone.” Statista, March 5, 2025.

To fulfill its strategic responsibilities, Europe must invest in deterrence systems and strategic enablers to both deter, and, if necessary, defeat a major-power aggressor (Grand, 2024). Presently, the EU faces persistent shortfalls across land, naval, and air domains (Kilic, 2024: 44), as well as lacks critical enablers for sustained, large-scale operations, which remain largely supplied by the U.S. (Rough & Kasapoğlu, 2025) The EU Commission has addressed these challenges by committing to invest in priority capability areas under the ReArm 2030 plan, including air and missile defense, artificial intelligence and electronic warfare, and strategic enablers (Bissacio, March 27, 2025). Giegerich and Schreer provide a similar listing. Europe, they suggest, needs to work on several parallel tracks—invest in its strategic deterrent, exploring the opportunity for a nuclear umbrella under French-British leadership—an option that might consider increasing the number of nuclear warheads and a new dual-capable aircraft arrangement for Europe. In conjuction, the bloc should build up conventional-strike arsenals in Germany and other non-nuclear states, invest in long-range ballistic and hypersonic missiles, big data, advance command and control structures within NATO for EU-only operations, and bring about interoperability, and so forth (2025). “Finally, a core group of European countries must be willing to take the lead within NATO and the European Union.” Additionally, Europe, according to Budginaite-Froehly, needs to refine the EU-NATO alignment on defense to eliminate vulnerabilities on logistical interoperability, revamp the dysfunctional defense industrial base to scale up European rearmament, and close the capability gaps, especially in air defense (2025). Noting that the Union has achieved some recent successes in acquiring some major enablers, such as a joint fleet of seven tanker aircraft in Eindhoven (the Netherlands) or the German-led European Sky Shield Initiative focused on air and missile defense (Grand, 2024: 18). Since 2024, meanwhile, some NATO Europe members have been working on a collaborative project to develop ground-launched cruise missiles, independently of U.S.; some others possess weapons equal to or many times better than Russia, not mentioning the fact that France and UK are nuclear powers (Brad Lendon, CNN, March 7, 2025). The Polish Eastern Shield, a strategic project launched in 2024 to deter conventional attacks through surveillance, mobility infrastructure and physical obstacles, could also, as the EU leaders referred to, become a key element in ensuring Europe’s security and protecting its population from potential external threats (Council of EU, April 3, 2025).

Beyond these shortcomings, Europe faces industrial and procurement challenges stemming from structural factors, slow processes, and constraints within the EDF, which hinder the Union’s ability to convert defense spending into effective military capabilities, while also generating inefficiencies, system duplications, and missed economies of scale. The EU defense industry remains fragmented and underdeveloped; defense cooperation is managed in intergovernmental basis; future major structuring projects are yet to be launched; and the degree of national control is extremely high (Lefebvre, 2024: 4). The U.S. industrial base, from its part, is unable to meet the demand, lagging behind in processing orders due to skyrocketing demand that hit the record in sales in 2024 (Hursch & Taylor, 2025). The EU Commission disbursed $541.1 million last year to scale up the ammunition production capacity to 2 million shells by the end of 2025 as part of a broader $2.1644b initiative to revamp the military-industrial complex (2024). The ReArm Europe intends to achieve such objective to deter Russia and break the EU dependency on U.S., as well as diverting funds from American industry to European suppliers (Sorgi et al., Politico, March 19, 2025). Equally important is enhancing cooperation in research and development (R&D) and collaborative procurement. Currently, such cooperation remains limited and largely organized along national lines, as there are no effective mechanisms to enforce coordinated or joint purchases among member states despite existing defense planning processes (Scazzieri, 2025). Last year witnessed a “temporary slowdown” in collaborative procurement—with only 6 percent of R&D expenditure allocated to joint efforts. The Franco-German project for a next-generation aircraft—the Future Combat Air System (FCAS) and the Main Ground Combat System (MGCS) illustrates how disagreements can lead to long delays and jeopardize ongoing initiatives (Id.). To address these challenges, the EU Commission committed $169b via the SAFE instrument to foster joint procurement projects, alongside $9.4624b pledged by the EDF for collaborative defense research and capability development for the 2021-2027 period (EU External Action, 2022). So far, most of additional military spending, as Taylor found out, has been uncoordinated and national, and less on collaborative projects and from European suppliers, showing “a big gap between rhetoric and reality.” (2024). A collaborative solution involving all relevant parties—the U.S., NATO, and European-American manufacturers—as Hursch & Taylor suggest, is essential to address vulnerabilities and loopholes in the industrial and procurement sectors. This includes enhanced support among allies, such as removing bureaucratic hurdles to accelerate procurement procedures. The American involvement in these processes remains critical (2025).

Last but not least, EU faces deep political divisions regarding both threat perception and strategic autonomy. The EU countries have different perception threat: traditionally, Eastern European states have relied on NATO to defend from Russia they see as the primary existential threat same as the Nordic countries, involving Finland and Sweden; the southern member states focus on instability in North Africa and Middle East they see as a danger to their national security, whereas others, Ireland and Austria, maintain the position of neutrality (Budginaite-Froehly, 2025). European countries, also, have historically held different views on strategic autonomy. Whereas France has championed efforts toward enhanced defense autonomy, Germany and many Eastern states remain cautious about initiatives that tend to weaken or undermine NATO authority. Nevertheless, this trend is changing. There is an increasingly political will within EU countries, especially in France, Germany, and some others, toward a more integrated European defense since the war in Ukraine. Numerous obstacles, as mentioned above, have contributed to, or prevented Europe from achieving a greater strategic autonomy, therefore creating an autonomous army, independent from NATO, including as follows: the idea of preserving NATO’s integrity and its primacy on defense, concerns over the Atlantic Alliance’s fragmentation and to avoid costly duplications/replications; preferences of some countries to trust NATO for collective security, a general unwillingness of some others to surrender sovereignty over national forces, and the neutrality policy of others (Graf von Kielmansegg, 2019); fear of failure as in case of the EDC; and the conviction that there is no imminent threat, thus, a military initiative would rise global tensions (Castiglioni, 2025).

EU Strategic Autonomy and the Feasibility of a European Army

Donald Tusk: “Hear for yourself how it sounds, 500 million Europeans begging 300 million Americans to defend them from 140 million Russians who have been unable to overcome 50 million Ukrainians for three years.” Daniel McCarthy, New York Post, March 3, 2025.

This section weighs arguments over strategic autonomy and the feasibility of building a standing European army. Proponents support the EU ambitions for an autonomous army as a means to defend European territories, reduce EU dependency on U.S., and improve the continent’s geopolitical standing. Europe, they suggest, should take greater responsibility for its defense in response to new security environment and the prospect of less American involvement in continent, encompassing four pillars: resilience and cyber defense, military mobility, research and development, and capability development and delivery (Grand, 2024). Critics, however, highlight Europe’s lack of means and capabilities to achieve strategic autonomy. The EU lacks a permanent military headquarters, a centralized command system, and/or integrated forces capable to conduct high-intensity operations independently, and as the Ukraine’s war unfolded, European support often remains reactive, fragmented and dependent on NATO and the U.S. leadership. Instead, they propose a greater defense cooperation and a strengthened EU pillar within NATO. Strategic interdependence vs. strategic independence.

For advocates of strategic autonomy, Europe does have means and capabilities to defend its territories. It does have the economic and technological power, as well as funding to rebuild its defense capabilities, strengthening its technological and industrial complex, and building a full-spectrum force alongside the combat support contingencies (Bergmann, 2025; Grand, 2024). Economically, as Grand argues, Europe’s combined GDP is ten times larger than Russia’s, and second only to the U.S.; the EU-NATO combined defense forces are bigger than Russia’s or U.S.; the European NATO countries and the EU member states together outspent Russia four to one on defense in 2023; and European defense industries produce some of the most advanced weapons systems around—with five European countries being among top ten global arms exporters (2024: 2). Besides, Europe maintains the primary position in global trade as first trading partner and first foreign investor; its GDP was close to that of North America in 2024, growing 1.8 percent for a decade against the 2.4 percent of North America; and demographically, Europe is home to half a billion people (EU Trade and Economic Security, 2025). Hence, funding, as Bergmann points out, is not the problem, for EU countries now spend over $100b per year on defense more than they did in 2019, a figure that could change adding Finland and Sweden to the equation—besides $169b pledged through the SAFE instrument (2025). Moreover, the entire bloc has nearly two million uniformed personnel and spends roughly $338b per year on defense, more than enough to deter Russia and enough to make Europe collectively a military power. The problem with European defense, this author highlights, is not about spending but its tremendous structural problems, its fractured defense posture consisting of 27 bespoke militaries—not designed to defend Europe. “It is good that Europe is thinking big when it comes to funding, but they also need to think big when it comes to reform and integrating Europe’s forces.” (Id.)

Thereupon, a full-fledged force not only enhances Europe’s geopolitical and economic influence, it also helps the Union assert itself as a global security provider, while reducing its dependency on U.S. and other allies. To attain strategic autonomy, the Union, based on experts’ analysis, should embrace the paradigm shift that requires from member states to be actively prepared to defend Europe’s new security environment with less American engagement (Bergmann, 2025; Grand, 2024). That entails focusing—in the short-term—to deter Russia from attacking European territories parallel to supporting Ukraine’s war efforts and humanitarian needs while depleting Russia, addressing major defense vulnerabilities and shortfalls, especially in areas heavily reliant on U.S., and accelerating the pace of ammunition production. In the long-run, Europe should embark a robust, ten-year sustained plan—developing a full-force package side by side with combat support capabilities and key enablers to back European forces, air transport and tankers, intelligence and targeting capability, currently provided primarily by the U.S. (Grand, 2024: 1-13) “Such an objective is achievable and fiscally sustainable […].” (Id.) The common European force, Bergmann follows, should be able to act and fight as one to defend the region and replace the U.S.; it should be more of a hybrid force, belonging to EU collectively—as the one agreed to at St. Malo—with the responsibility to intervene in regional, but not in international crisis (2025). Further, EU needs a unified command system, a permanent military headquarters, and a supreme European commander to command both—the common European force and national militaries—which are doable and don’t require changes to the European treaties (Id.). “These efforts should be Europeanized as much as possible and done at the EU level.” Lastly, EU, according to Castiglioni, should revisit lessons from the EDC and develop a Defense Union that takes into accounts the Brussels’ present geopolitical, institutional, and technological landscape. First, by establishing the European Defense System (EDS), composed of national militaries as the main building blocks, and then by developing a rapid deployment force as the embryo of a European federal army—operating under a common command and control (2025).

For opponents, on the other side, the realization of strategic autonomy, including a European army, is politically and practically unfeasible, for such an enterprise requires a great deal of time, efforts and resources, and a unified political will, which Europe currently doesn’t have (Graf von Kielmansegg, 2019; Meijer & Klein, 2025; Rough & Kasapoğlu, 2025). Therein, ideas that tend to revive the EDC—are viewed as misleading. Momentarily, the ambitions and the scope of the new European defense initiatives are limited (Graf von Kielmansegg, 2019). Besides, there are political obstacles, namely the degree of political unity and nuclear option (Lefebvre, 2024), and fears over sovereignty that make strategic autonomy an illusion—with the nuclear capability being as the most complicated one (Arthur Bertényi, Euro Prospects, February 24, 2023). As Lefebvre put it, “If Europeans were to move toward an autonomous European defense, they would have to settle the question of nuclear protection, otherwise this alliance would be of little value against Russia.” Even if the Union has a political will, structural problems concerning fractured defense industries that operate along national lines and limited production capacity prevail (Hursch & Taylor, 2025). One, Europe’s defense industrial base is ill-equipped to produce capabilities that strategic autonomy demands. The SAMP/T is an example—the production of only one missile for the system’s principal interceptor, the Aster, took—until recently—up to forty months; even if time is shortened and invested more, the SAMP/T can hardly compare with the U.S.-made Patriot or French Rafale (Rough & Kasapoğlu, 2025). Two, lack of strategic enablers, particularly in the air domain—crucial for executing sustained large-scale combat operations, as well as lack of high-end weaponry (high-end kinetic combat and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance drones, to name a few) limit the possibilities of European strategic autonomy, rendering it an interesting concept for further development at the moment, but with no practical applicability in the short-to-medium term (Id.). “The only feasible way to do this is to work with the United States. Strategic autonomy is built over decades, not declared in a day,” Rough and Kasapoğlu argue. Most importantly, a fully integrated EU force requires from political leaders to transfer “their military instruments” to the Union through a long and costly integration process, and, also, amending treaties on national security and territorial defense matters—which are politically and practically infeasible (Meijer & Arjen, VerfBlog, March 6, 2025). As Budginaite-Froehly put it, “The EU, for its part, still lacks both formal competencies and a unified political ambition to step deeper into the defense planning and execution field.” (2025)

Arguably, one of the main obstacles for Europe to obtain strategic autonomy has been United States. Since the 1990s, U.S. has opposed efforts on strategic defense, fearing that a powerful EU could challenge NATO authority—a strategic mistake that has undermined both the EU and NATO credibility (Bergmann et al., 2021). For some, European strategic autonomy is still very much about U.S., which has “played a more ambiguous part”—by pressuring Europeans to pay more on defense via NATO, while simultaneously, objecting initiatives that led toward that achievement (Bergmann et al., 2021; Quencez, 2021). Bergmann et al. call the U.S. policy approach a “grand strategic error” and fundamentally a failure of its post-Cold War strategy toward Europe that weakened NATO militarily, strained the trans-Atlantic alliance, and contributed to the relative decline in Europe’s global clout (Id.). “As a result, one of America’s closest partners and allies of first resort is not nearly as powerful as it could be.” It remains unclear, therefore, if this project is more likely to keep U.S. engaged or disengaged in Europe (Quencez, 2021). For the future of transatlantic relationships, Europe’s strategic autonomy has been deemed “necessary but impossible.” (Kundnani, 2018) That said, the U.S. involvement in such endeavors is crucial to contribute in reformation and adaptation of transatlantic security partnership. By enhancing strategic autonomy, as proponents claim, EU could positively contribute to the European-Atlantic security and complement NATO efforts in this respect—an ambitious vision that, according to Csernatoni, is yet to be fully translated into collective political will and concrete actions. The ongoing war in Ukraine, on the other hand, have only consolidated the primacy of NATO in collective defense, highlighting the centrality of America in European security and defense—in terms of both (geo)political leadership and operational support (Dempsey, 2023). As Andrew Cottey from the University College Cork put it, “Real autonomy from the United States on defense would require significantly increasing defense spending and/or much deeper integration—a Euro moment—in defense. EU member states have not been willing to take on these steps.” (Id.)

For now, all options are on the table: cooperation, integration, or starting new. The proposals range—from those calling for a European army—to those suggesting a more realistic solution—a cooperative network of national armies under the concept of pooling and sharing as the existing programs set out (Graf von Kielmansegg, 2019) to those favoring a stronger EU pillar within NATO. Others propose an incremental approach, establishing—according to present treaties—a complementary force that enhances national capabilities, advances cooperation, and is based on a coalition of the willing under intergovernmental decision-making as in case of Frontex. An option that nonetheless may face obstacles of the unanimity necessitated in defense affairs (Meijer and Klein, VerfBlog, March 6, 2025). So far, however, creating a stronger EU pillar within NATO remains the most viable solution. Strategic interdependence vs. strategic dependence. Alongside, in a ten-year timeline, building a common European standing force—composed of the biggest national militaries as the backbone of European defense, France, Germany, Poland, and UK, if it will—supported by frontline states, Finland and the Nordic-Baltic states. A standing European force with the goal to operate as cohesively as possible (Bergmann, 2025).

Since Federica Mogherini, former EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, made strategic autonomy a core to the EUGS, the notion has sparked debates and cast skepticism arising from vagueness and circularity of the definition (Torreblanca 2023; Kilic, 2024) to its reactive, inward focus. As a matter of fact, the concept has always been viewed as amorphous and rhetorical—whose delivery is impossible as it demands a significant increase of defense spending and/or much deeper integration that EU has been unwilling to take on. There is also a long gap between rhetoric and delivery (Dempsey, 2023). Capability is a prerequisite for strategic autonomy, which Europe lacks momentarily, most notably, it has shortfalls in land, naval, and air domains (Kilic, 2024: 44). In essence, strategic autonomy is a defensive notion, for it sends the wrong message to the world and divides EU—casting fears to some that strategy would strengthen the economic-industrial power of France and Germany whilst weakening their own. (Torreblanca, 2023). Rather, strategic interdependence is considered not only inevitable but a desirable option. As Torreblanca put it, “Strategic autonomy is a reactive strategy to confront today’s challenges; strategic interdependence is a proactive way to meet Europe’s needs and overcome the limitations of strategic autonomy.” Strategic autonomy is about Europe, strategic interdependence is about Europe in relation to others; strategic autonomy is not the solution, interdependence is (Id.).“Strategic interdependence would increase the autonomy of the EU, its member states, and its allies and partners. It would help states maximize their growth and wealth, and thus their power base. It would also enhance their security, and therefore their sovereignty.” (Id.)

A Strengthened European Pillar within NATO: Supplement, Not Replacement

Building a stronger EU pillar within NATO represents a feasible and sustainable solution. The future defense of Europe and the advancement of its global interests depend on a strengthened European military capability within NATO (Budginaite-Froehly, 2025; Castiglioni, 2025; Taylor, 2024). As such, EU can become a strategic player in defense alongside NATO by embracing the role of a defense enabler—aligning NATO’s targets with EU defense initiatives. The EU-NATO complimentary roles remain crucial; the two organizations have co-existed in a modus vivendi—as formulated at the 1999-NATO Washington Summit (Budginaite-Froehly, 2025). However, now is the time for EU-NATO to move their relationship to the next level, redefining their roles in response to new security environment and the U.S. pivot toward Asia and Indo-Pacific. That would imply recognizing both the unique and leading role of NATO’s command structure and defense planning and the EU’s new role as a security player and its unique set of regulatory and financial tools (Grand, 2024). The EU-NATO, as Grand suggests, should expand cooperation to coordinate issues of mutual interest, i.e. standards, innovation, military mobility, and cyber; aligning to the maximum extent possible NATO and EU capability development efforts to ensure coherence between EU efforts and NATO defense planning priorities; allowing a quasi-systematic cross-participation of staff (as non-voting invitees) in relevant committees and working groups, and so forth (Id.). “More broadly, as a more European NATO emerges, the two organizations need to refine the concept of the European NATO pillar. This should not be an EU caucus but rather a European pillar that combines burden sharing and responsibility sharing.”

Under the existing but rarely used Berlin Plus arrangements, EU could use NATO command structures rather than replicating a separate chain of command. Hereupon, a new deal EU-NATO to reset relationship between two Brussels organizations is needed (Taylor, 2024). Consultations on a step-by-step change in the EU-NATO partnership and better interorganizational communication, with the involvement of non-EU allies, are essential to avoid unnecessary duplications and ensure the respect of the principle of no-decoupling (Budginaite-Froehly, 2025; Taylor, 2024). One thing must be clear: a strengthened EU defense, as Bergmann et al. clarify, doesn’t in any way mean replacing or displacing NATO, a stronger EU defense doesn’t aim to weaken or undermine NATO credibility and its role on collective defense, for “NATO and EU defense are incompatible and at odds, the EU and NATO are not opposing organizations, they are, in fact, fundamentally tethered.” (2021) NATO has been the cornerstone of Europe’s defense architecture since the end of World War II, providing collective security through Article 5 on mutual defense. Therefore, strategic autonomy should be seen as a supplement, not a replacement for NATO. If a European pillar were to be created, Europe would need to set up a unified command structure and command headquarters in NATO—with a European commander-in-chief commanding both the EU force and the national militaries. The top EU Commander could be dual-hatted—the deputy NATO commander, too, commanding the EU current missions under its command (Bergmann, 2025).

Conclusion: Toward a Stronger EU Pillar in NATO and a European Force

This article traced Europe’s long journey toward building a security and defense establishment, examining the EU capability and operational domains while exploring the concept of strategic autonomy and the feasibility of a European autonomous army. Europe could have established its own force immediately after World War II were it not for deep political divisions over national sovereignty in defense affairs—disagreements that persist to this day. Rather than emerging as a global defense actor, Europe remains fragmented, with militaries largely uncoordinated and not designated to defend the continent. Yet, the onset of the war in Ukraine, coupled with the prospect of potential Russian aggression and the possibility of American disengagement, has intensified political will across the Union toward greater defense integration. Concerns over U.S. withdrawal, meanwhile, have made strategic autonomy more urgent than ever (Castiglioni, 2025).

As argued, Europe has developed a robust defense infrastructure, including strategies, initiatives, and frameworks aimed at building security and military structures whilst strengthening its capability dimension. Consequently, the EU has assumed a global security provider role through launching over thirty civil-military operations since the 2000s, ranging from humanitarian assistance to crisis management to rule-of-law missions. The evolution of the CSDP has been shaped by both external geopolitical shocks and endogenous institutional factors that influence the Union’s allocation of resources and choice of instruments (Rutigliano in Beaucillon et al., 2023; Kilic, 2023). Initiatives such as ReArm Europe reflect these pressures. Yet, despite notable progress in security and defense policy, the CSDP remains limited to small-scale missions; in other words, it does not ensure the collective defense of Europe. Even with the Lisbon Treaty’s adoption of a collective defense clause, the EU lacks a legal mandate to conduct large-scale military operations, leaving NATO as the primary guarantor of European security.

Europe now faces an urgent imperative to assume greater responsibility for its own security and emerge as a global defense actor alongside NATO. In the short-term, this requires sustained investment in critical capabilities, reinvigoration of the industrial and technological base, enhanced collaborative procurement, and bolstered military budgets. Concurrently, the EU must continue supporting Ukraine and deter potential Russian aggression in European territories. In the long-term, the Union should prepare to establish a common standing force, capable of both deterring Russia and addressing the security vacuum that could arise from a potential American disengagement. While multiple pathways exist, combining a strengthened EU pillar within NATO in the near-term with the gradual development of a full-spectrum European force in the long-term appears to be the most feasible strategy. Time is now: Europe possesses the means, technology, power, and resources to achieve this vision.

REFERENCES

Bergmann, Max. 2025. “Why It’s Time to Reconsider a European Army.” Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Bergmann et al. 2021. “The Case for EU Defense: A New Way Forward for Trans-Atlantic Security Relations.” Center for American Progress.

Berlin Plus Agreement—Provided by Tim Waugh. NATO. 2003. Brussels. Belgium. Accessible at: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cmsUpload/03-11 11percent20Berlinpercent20Pluspercent20presspercent20notepercent20BL.pdf.

Brady et al. 2025. “Can Ukraine Fight Without U.S. Aid? Seven Questions to Ask.” Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Budginaite-Froehly, Justina. 2025. “The EU Must Become a Strategic Player in Defense—Alongside NATO.” Atlantic Council.

Camille, Grand. 2024. “Defending Europe with Less America.” European Council on Foreign Relations. Pol. Brief ECFR/545.

Castiglioni, Federico. 2025. “A New European Defense Community: The European Defense System.” European Movement International.

Chahri, Samy. “European Missions and Operations Abroad.” European Parliamentary Research Service. PE 762.478. October, 2024. Brussels, Belgium. Accessible at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2024/762478/EPRS_BRI(2024)762478_EN.pdf.

Defense Industry Europe: “EU Defense Ministers Approve 2024 CARD Report, Emphasize Collaboration and Capability Development.” November, 2024. Brussels, Belgium. Accessible at: https://defence-industry.eu/eu-defence-ministers-approve-2024-card-report-emphasise-collaboration-and-capability-development/.

Dempsey, Judy. 2023. “Judy Asks: Is European Strategic Autonomy Over?” Carnegie Europe. Accessible at: https://carnegieendowment.org/europe/strategic-europe/2023/01/judy-asks-is-european-strategic-autonomy-over?lang=en.

European Defense Community Treaty. 1952. Convention on Relations with the Federal Republic of Germany and a Protocol to the North Atlantic Treaty.” Pages 167-251. U.S. Government. June 2nd, 1952. Washington: D.C.

European Union Global Strategy. “Shared Vision, Common Action: A Stronger Europe.” 2016. Brussels, Belgium.

EU High Representative for Foreign Policy. “A Strategic Compass for Security and Defense.” 2022. Brussels, Belgium.

EU Commission. “Joint White Paper for European Defense Readiness 2023.” March 2025. Brussels, Belgium.

European Union External Action. “The Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP): The Shaping of a Common Security and Defense Policy.” March 28, 2022. Brussels, Belgium. Accessible at: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/shaping-common-security-and-defence-policy_en.

European Commission. “The Commission Allocates €500 Million to Ramp up Ammunition Production, out of a Total of €2 Billion to Strengthen EU’s Defense Industry.” Press Release. March 15, 2024. Brussels, Belgium.

European Union External Action. Security and Defense Policy Fit for the Future.

March 29, 2022. Brussels, Belgium. Accessible at: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/european-defence-fund_en.

European Parliament. “The Lisbon Treaty: More Powers for the Parliament.” Brussels, Belgium. Accessible at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/about-parliament/en/parliaments-powers/the-lisbon-treaty.

Farinha, Ricardo. 2025. “The EU Common Security and Defense Policy: Moving Away from Democracy Support.” Carnegie Endowment.

Fedrigo, Lorenzo. “Deja Vu: The Case of the European Defense Community.” BACKGROUNDERS. April 23, 2025.

Giergerich, Bastian & Ben Schreer. 2025. “Without the US It’s All About Us in European Defense.” IISS.

Hursch, James & Kristen Taylor. 2025. “Revitalizing the US Defense Industry is Best Done with European Allies.”Atlantic Council.

Kilic, Seray. 2023. “Half-Hearted or Pragmatic? Explaining EU Strategic Autonomy and the European Defense Fund Through Institutional Dynamics.” Central European Journal of International and Security Studies. Vol. 18, Issue 1, pp. 43–72. DOI: 10.51870/FSLG6223.

Larivé, Maxime, H. A. 2019. “The Western European Union (WEU).” Oxford Research Encyclopedias. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1093.

Lefebvre, Maxime. 2024. “Has the Time Come for European Defense.” Schuman Paper n°743. Robert Schuman Foundation.

Maślanka, Łukasz. 2025. “The White Paper: The EU’s New Initiatives for European Defense.” Centre for Eastern Studies. Accessible at: https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2025-03-27/white-paper-eus-new-initiatives-european-defence.

NATO. Washington Summit. April 23, 1999. Last updated on November 6, 2008. Brussels, Belgium. Accessible at https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_27286.htm.

Polish Presidency of the EU Council. “European Defense Ministers Meet in Warsaw to Discuss Continental Security.” April 3. 2025. Brussels, Belgium.

Quencez, Martin. 2021. “The U.S. Cannot Escape the European Strategic Autonomy Debate.” Foundation for European Progressive Studies.

Rittimann, Olivier. 2025. “Operation Althea and the Virtues of the Berlin Plus Agreement.” NATO Defense College. Policy Brief 02-21. Accessible at: https://www.ndc.nato.int/news/news.php?icode=1521#.

Rough, Peter & Can Kasapoğlu. 2025. “European Strategic Autonomy is An Illusion.” Hudson Institute.

Rutigliano, Stefania in “The Russian War Against Ukraine and the Law of the European Union.” Ed. by Beaucillon et al. Ukraine Conflict’s Impact on European Defense and Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO). European Papers. ISSN 2499-8249 Vol. 8, 2023, No 2, pp. 765-777.

Torreblanca, José Ignacio. 2023. “Onwards and Outwards: Why the EU Needs to Move from Strategic Autonomy to Strategic Interdependence.” European Council on Foreign Relations.

University of Pittsburg. “Archive of European Integration (AEI).” Accessible at https://aei.pitt.edu/westerneuropeanunion.html. Pennsylvania. U.S.

- [i] Deja Vu: The Case of the European Defense Community

- BACKGROUNDERS – April 23, 2025, By Lorenzo Fedrigo

Leave a comment