Sebahate J. Shala

Despite significant progress in prosecuting war crimes and establishing judicial truth through international and domestic courts, Bosnia and Herzegovina lacks a unified curriculum that systematically addresses large-scale human rights violations and genocide committed during the 1992–1995 war. Education system remains fragmented along ethnic and administrative lines, resulting in competing or absent narratives of the past. The omission or selective treatment of historical facts obstructs the development of a shared truth, reinforces politics of denial, and hinders reconciliation. Consequently, the continued absence of history teaching on mass atrocities constitutes a violation of international human rights law, including the right to education, the rights of the child to education, peace, and nondiscrimination, the right to the truth, and guarantees of nonrepetition.

The core problems of education are embedded in the state structure and political system stemming from international peace accords that institutionalized ethnic and administrative divisions. The absence of a comprehensive transitional justice strategy, particularly a national truth-telling commission, linking human rights–based education to transitional justice objectives has perpetuated parallel and exclusionary interpretations of history. Despite long-standing policy recommendations, segregation and discriminatory practices in education persist—even where they have been ruled unlawful. Internally, the fractured education system and divergent history curricula undermine critical reforms and effective history teaching, exacerbate ethnic divisions, and impede social cohesion and reconciliation—ultimately threatening the stability of the state. Externally, these dynamics contribute to broader regional destabilization (Reynolds, 2017). Education, intended to produce knowledge and advance human rights, has thus become complicit in their violation, reproducing contested truths and false narratives that extend beyond classrooms.

This article examines the relationship between education, truth, and human rights in Bosnia and Herzegovina, emphasizing structural and political factors as central to shaping interpretations of the country’s violent past. By linking education to international human rights standards and transitional justice objectives, it highlights the consequences of the absence of an inclusive transitional justice strategy and a national truth-seeking mechanism. The article concludes by proposing policy-oriented reforms to history teaching and broader transitional justice processes as essential to reconciliation and guarantees of nonrepetition. A justice-sensitive and pluralist approach to education requires the abolition of segregation and discrimination, school integration, curriculum harmonization, critical engagement with past legacies, and the inclusion of multiple historical perspectives. Ultimately, the endorsement of a national transitional justice strategy and a truth-telling commission—supported by inclusive political and social dialogue involving state authorities, civil society, victims’ families, and survivors—is imperative.

Theoretical and Legal Framework: Education as a Tool for Peace and Conflict Prevention

Recognized under international human rights law, education is both a fundamental human right and a foundational pillar for advancing human rights, peacebuilding, and conflict prevention. The purpose of education system, as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1949) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966) stipulate, should be to strengthening human rights and fundamental freedoms and to promoting understanding, tolerance, and friendship among all people, while contributing to the maintenance of peace. The Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) guarantees “the right of the child to education” and “nondiscrimination,” emphasizing that learning spaces should prepare children for a responsible life in a free society, grounded in understanding, peace, tolerance, equality, and friendship among all peoples. Given the importance of human rights–based education in societies in transition, transitional justice processes should be addressing the full spectrum of economic, social, cultural, political, and civil rights to foster accountability and the rule of law (UNGA, 2012). The UN Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to Remedy and Reparation (UNGA, 2005) explicitly link education to transitional justice goals, calling for the inclusion of accurate accounts of past violations “in educational material at all levels” and “for the provision of human rights and international humanitarian law education across society.” (Cole, 2017) The justice-sensitive history education also enables the realization of the right to the truth, which the Human Rights Council acknowledges as essential to combating impunity and protecting human rights. Accordingly, the state bears the duty to preserve, protect, and ensure access to archives and documentation of wartime abuses as well as integrate this knowledge into education system in support of accountability, rule of law, and guarantees of nonrepetition (UNGA, 2012).

Beyond being a fundamental human right and a basic necessity, education is viewed as critically important to peacebuilding, conflict prevention, and transitional justice (Nesterova et al., 2024), and a crucial component to promote civic engagement and tolerance, while fostering international understanding and dialogue across diverse communities (Davies, 2017; UNESCO, 2025). Research indicates that proactive engagement with the legacies of the past can play a transformative role (Ramirez-Barat and Duthie, 2015) and serve as a catalyst for conflict transformation and sustainable peacebuilding (Nesterova et al., 2024), as school spaces enable shape new norms, challenge contending narratives of the past, and promote respect for human rights and rule of law. Henceforth, critical and thoughtful teaching, as Nesterova et al. suggest, should be focused on two objectives: transforming people’s attitudes, values, and behaviors and transforming and building inter-group relationships (Id.). Correspondingly, a critical approach to history, as George put it, “contributes to truth-sharing, official acknowledgement of harms and suffering, recognition of survivors and preservation of their memories, and fosters restorative justice.” (2007) From a victim-centered perspective, historical teaching lays the groundwork for reconciliation and collective healing as it “increases the visibility of victims and their descendants, recognizes their suffering, humanizes their experience, and highlights their agency and resilience.” (UNESCO, 2025) Conversely, selective omission or divergent history curriculum threatens—not only collective forgetting and violence recurrence (Velez, 2021) but also reinforces the opposing history interpretations, encouraging the politics of denial, and impeding efforts for reconciliation and healing (Ramirez-Barat and Duthie, 2015). In sum, education, as some cases have shown, holds potential to both fueling conflict and increasing prospects for peace (Cole, 2017).

The conflict-sensitive history education has—until the past two decades—been an underdeveloped theme and a missing pillar from transitional justice programs despite its acknowledged positive impacts to human rights and transitional justice areas (George, 2007; Davies, 2017). The discussions center around proposals advocating the alignment of history education with transitional justice objectives or its integration in transitional justice strategies. Arguably the inclusion of explicit and implicit curriculum of past injustices contributes to overall transitional justice goals—including truth-telling, accountability, and guarantees of nonrepetition—key for building just and peaceful societies based on principles of human rights and rule of law (Cole 2007; Velez, 2021). Transitional justice approaches to education, as Davies emphasizes, can shift education from being part of the problem to being part of the transition to a more peaceful society considering the importance of truth-seeking or the acknowledgment of the truth to education system and the entire society in general (2017). Furthermore, the sensitive-justice history learning is closely connected to truth-telling complementing transitional justice mechanisms and helping prevent conflict recurrence. Studies examining the truth-seeking commissions in Columbia highlight the educator’s role in these processes, indicating that truth positively impacts both individual and societal levels. Truth-telling is considered a “necessity” and crucial for “making things right for humankind and for society,” particularly for victims and survivors, linking it directly to justice, change, and healing (Velez, 2021). That said, an integrated approach to education not only enables the society to engage in dialogue on the dealing with the past but also encourages education reforms from a human-rights-and-democracy-and-rule-of-law standpoint, recognizes the victims’ right to the truth and reparations, so the education itself, as Ramirez-Barat and Duthie argues, can become an institution committed to the guarantees of non-recurrence (2015). Lastly, truth-seeking can be important to conflict prevention and recurrence (Mendeloff, 2004) and increased societal trust (Fiedler and Mross, 2023) but only in combination with broader societal approaches such as victim restitution with amnesties or truth-finding and/or bridge-building activities.

The education system reforms in transition societies have shown mixed results, therefore, a context-specific approach to transitional justice is recommended to avoid potential harmful consequences. While initiatives to integrate schools in Northern Ireland have been partially successful, Rwanda and Bosnia and Herzegovina continue the segregation and discrimination practices—same as Sri Lanka (Davies, 2017). The South Africa transformation process—known as “the most far reaching reform” to date—on the other hand, has not helped break the post-apartheid socio-economic inequalities (Risana Ngobeni et al., 2023). The country embarked into a comprehensive education reform process, comprising—among others—measures including geographical restructuration of education departments, creation of a non-racial department, new national curriculum and textbook revisions, and the increase of funding and the redistribution of resources (Ramirez-Barat and Duthie, 2015). The inclusion of truth-commissions and court proceedings in school curricula remains limited, too. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa pioneered the model of using findings to reshape the national history curriculum, the Guatemala Commission for Historical Clarification provided recommendations for education purposes as did Sierra Leone. The latter introduced a creative model to truth-sharing in education sector, incorporating in its truth-seeking commission’s mandate the production of materials specifically for either school-based or non-school based education for the youth (George, 2007).

Bosnia and Herzegovina: Education as a Driver of Segregation and Ethnic Division

Bosnia and Herzegovina exemplifies a particularly complex post-conflict situation—where ethnonationalist and political divisions continue to shape political and social life (Raynolds, 2017; UNGA, 2022). The deep and persistent structural and social divisions—solidified through international peace agreements—have impacted all political, economic and public domains, including the education system (Bobo Kovač, 2025). The Dayton Peace Accords (1995) and the Bosnian Constitution institutionalized ethnic fragmentations drawn by conflict, creating a complex political structure to accommodate the warring parties while splitting the country in two federal entities—Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina with predominantly Bosnian and Bosnian Croats—and the Republika Srpska-Bosnian Serbs territory, including the autonomous Brčko District (Freeman, 2004). The political and legal framework set up the architecture of the new state but failed to provide a comprehensive vision of transitional justice, resulting in ad hoc and incomplete transitional justice initiatives, particularly relating to truth-seeking and reparations measures (Id.). Henceforth, transitional justice mechanisms, including truth-seeking, reparations, memoralization, and institutional reform, have been partially applied, reflecting the entrenched political and ethnic divisions (Ramirez-Barat and Duthie, 2015; Teksen, 2019). Initiatives to officially endorse a national transitional justice strategy have been unsuccessful due to ongoing political and ethnic disagreements (Haris Rovcanin, BIRN, July 13, 2021). Instead, Bosnia and Herzegovina relies on the Revised National War Crimes Strategy focusing specifically on processing war crimes while disregarding restorative justice mechanisms (OSCE, 2020). The absence of an inclusive transitional justice approach has further prevented the establishment of a statewide truth and reconciliation commission—capable to establish facts on the Bosnian war—contributing to fueling revisionism, creating parallel or absent interpretations of war, exacerbating ethnic divisions, and undermining reconciliation and healing (UNGA, 2022). Consequently, the alignment or integration of history education into transitional justice programs, particularly in truth-telling mechanisms, has never happened, thus perpetuating the distortion of the truth regarding the Bosnian war.

The organization of education sector directly reflects the state and administrative regulation and ethnic divisions defined by the constitution (Forić Plasto, 2020). Legally, the education system in Bosnia and Herzegovina is decentralized, providing the entity structures with the responsibilities over education matters, including the development of core curriculum, and harmonization and adaptation of educational curricula (Law on Primary and Secondary Education, 2003). Presently, there are three main education systems at each level of authority; the entities hold powers to determine the language of instruction and the content of the curriculum, involving the history teaching, with little or no control from the Federation (Forić Plasto, 2020; Wansink et al., 2025). In the absence of a state ministry of education to oversee and coordinate history teaching on state level, each department out of thirteen education departments across cantons, approves the use of textbooks and the curriculum. In some regions, meanwhile, guidelines on textbook use are provided by pedagogical institutes or educational inspectorates (Wansink et al., 2025). Although the Ministry of Civil Affairs handles, among others, the education matters, it is only responsible for coordination and consolidation of entity policies and, where required, connecting them to international strategies or activities (ECRI, 2024). Hence, most of the history curricula remain strongly ethno-national in orientation, exacerbating divisions and tensions between communities (Wansink et al., 2025). Under the “two schools under one roof” model, oftentimes, students “from different ethnic groups attend the same school but are physically separated,” they are taught in different languages and follow a specific ethnic curriculum (Ramirez-Barat and Duthie, 2015). Introduced as a temporary solution to reverse the post-war displacement and ethnic homogenization in some areas, the “two schools under one roof”—has unfortunately—become permanent—despite being outlawed and in violation of international and domestic human rights legislation (OSCE, 2018; UNGA, 2022). Efforts to create an integrated, inclusive education system and a more unified, state-level history teaching have largely failed (Wansink et al., 2025). Correspondingly, the education policy reform, supporting the end of segregation and discrimination, creating a harmonized, inclusive teaching, and incorporating multi-perspective history learning, have stalled. Disagreements regarding the extent, focus, and direction of reforms and—above all—lack of a political will and a dialogue between state institutions, political spectrum, and ethnic groups—have been the primarily obstacles (ECRI, 2024).

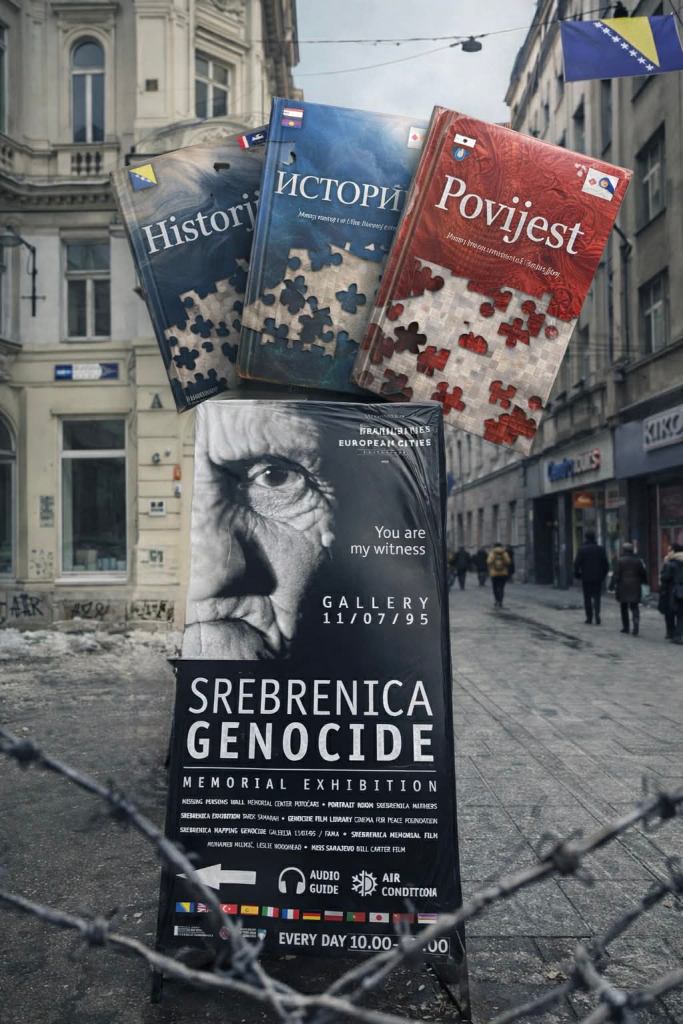

The fragmented education system and divergent history textbooks and curricula have contributed to opposing or absent interpretations of large-scale human rights violations during the Bosnian war, reinforcing politics of denial and obstructing the development of a shared truth (Reynolds, 2017; UNESCO, 2025). The glorification of war criminals and the denial of past atrocities have dominated post-war public discourse, permeating politics, military institutions, education, and broader society—despite being criminalized by the Office of the High Representative (Moore, 2022) and consistently condemned by international actors in Sarajevo (ICTJ, 2024). Furthermore, the absence of an inclusive transitional justice approach, particularly a national truth-telling commission, has enabled historical revisionism and the persistence of ethnonationalist wartime narratives, especially within the education system, thereby undermining efforts to acknowledge and institutionalize a shared, judicially established truth (UNGA, 2022). It is unanimously argued that the existing history curricula reinforces ethnic divisions, including school segregation and discrimination, creates false and biased historical accounts, fuels nationalism, and overall obstructs the development of a healthy, functional society (Bobo Kovač, 2025; Soldo et al., 2017). The history textbooks in three education systems, as studies have shown, offer a strong ethnically biased history interpretation—“us” versus “them”—all building a narrative of “celebrating us,” “devaluing them” and “being victimized by two other groups.” (Bobo Kovač, 2025) In an analysis examining the history textbooks of secondary education in two Bosnian Entities and in Serbia, BIRN found inaccurate and selective accounts relating to the 1990s Bosnian war. Each ethnic group approached war from their perspectives, omitting the established judicial facts while providing wrong classification of the major events, the number of killings, and the personalities involved. Whereas the history textbook of Bosniak and Croat-dominated Federation hold the Bosnian Serb Army responsible for the Srebrenica massacres, the Republika Srpska textbook omitted entirely the Srebrenica genocide, listing it among “mass crime locations,” while portraying the convicted war criminals, Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić, as heroes and leaders of national liberation (Mladen Obrenovic, BIRN October 30, 2020). In 2025, the Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina outlawed new textbook revisions introduced in Republika Srpska for presenting false historical accounts that distorted facts established by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) (Lejla Memcic, BIRN, January 24, 2025). The current history curricula and textbooks in Bosnia and Herzegovina not only violate international and domestic human rights standards but also fail to uphold the universal principles of a democratic society, active citizenship, and social participation, while discouraging the development of critical thinking, creativity, and active learning (Soldo et al., 2017; ICTJ, 2024).

History Education and the Risks of Collective Forgetting, Denial, and Impeded Reconciliation

By reproducing ethnically exclusive narratives, education reinforces divisions and undermines the social conditions necessary for healing and reconciliation. The unilateral and selective approach to describing the Bosnian war increases mistrust among communities, hinders accountability for wartime atrocities, and threatens state stability, security, and economic prosperity (OSCE, 2018; ICTJ, 2024). Reconciliation in Bosnia and Herzegovina remains a highly challenging and contested issue due to political and social divisions despite numerous initiatives focusing on peacebuilding, trust restoration, inter-ethnic dialogue, and youth engagement such as the Marshall Legal Institute’s Inter-ethnic Reconciliation Program, the IOM’s Bosnia and Herzegovina Resilience Initiative (BHRI), and the Center for Peacebuilding (CIM) in Sanski Most. The reconciliation process requires time, profound changes in attitudes, and active involvement of state authorities, political leaders, and ethnic, religious, and national groups (Gačanica, Initiative for Monitoring the European Integration of Bosnia and Herzegovina). The available literature emphasizes identity politics, structural and political system challenges, and the perpetuation of denial, particularly regarding the Srebrenica genocide, as key obstacles to reconciliation (Avramović, 2017). The fractured education system and the absence of a shared educational engagement with the past appears as a significant contributing factor (Reynolds, 2017). Considering the education’s transformative role and intergenerational transfer of knowledge, lack of a harmonized history teaching not only impedes reconciliation and healing (Ramirez-Barat and Duthie, 2015) but also risks collective forgetting (Velez, 2021). The education system, thus, can become complicit in perpetuating selective memory and denial. The learning spaces hold the potential to influence both transitional justice and reconciliation by mediating, on the one hand, tensions between justice and truth-telling processes and historical memory, and “learning to live together” and education for social cohesion, on the other (Ramirez-Barat and Duthie, 2015).

Lastly, education system in Bosnia and Herzegovina has had a direct and lasting impact on the realization of international human rights and transitional justice obligations, which the country adheres to and is obliged to fully implement. The ethnically divided education system constitutes a violation of international and domestic laws—including the right to education, the right of the child to education, peace, and nondiscrimination, the right to the truth, and guarantees of nonrepetition. Besides, the segregated education contradicts the-2002 education reform objectives and the domestic law on primary and secondary education, ensuring, as the ministers of education stated, equal access to quality education in integrated, multicultural schools—free from any interferences—and upholding the rights of all children (Soldo et al., 2017). Furthermore, the fractured education and selective history teaching violates key international instruments, connecting education to human rights and transitional justice areas, namely the UNGA resolutions on human rights–based education and on combating impunity and promoting human rights, the UN Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation (2005), and the Updated Set of Principles for the Protection and Promotion of Human Rights through Action to Combat Impunity (2005).

Policy Recommendations: Justice-Sensitive and Pluralistic Approaches to History Education

Instead of overhauling the entire system, justice-sensitive (Davies, 2017) and pluralistic approaches to education (UNESCO, 2025) must be considered, encompassing, among others, multiple perspectives, proactive engagement with the historical past, human rights and democratic citizenship-based learning, and curriculum change and textbook revisions. The designers of transitional justice programs should acknowledge that there is no single truth or perspective in post-conflict settings—a component insufficiently approached through international interventions (Fischer, 2005). A justice-sensitive approach, as Davies suggests, incorporates the change or removal of old biased curriculum containing offensive material, creation of new historical records based on the victims and non-victors’ viewpoints, inclusion of human rights-and-democratic citizenship curriculum, and a critical approach to history teaching (Id.). From a transitional justice standpoint, change is necessary to build a common understanding on past human rights violations and actions to upheld those rights in the future; from the education perspective, change implies a deep understanding that both—the rights and the citizenship—must be promoted and protected by the law (Davies, 2017).

The UNESCO’s pluralistic approach to history education embodies the involvement of multiple perspectives, critical and thoughtful learning, and proactive engagement with the past legacies, enabling children to critically analyze historical research and shape contemporary discourse whilst confronting biased narratives and nationalist propaganda reinforcing history distortion and denial (2025). The overarching framework to education policy supporting critical and proactive engagement with violent pasts should be aligned with learning objectives, including as follows: strengthening historical literacy by establishing a clear historical understanding that is fact-and research-based, fostering multiple perspectives by including accounts of victim and perpetrator groups as well as affected populations, encouraging critical thinking by developing learners’ ability to resist disinformation, hate speech and distorted historical narratives, fostering human rights knowledge and awareness through learning on mass atrocities, and guaranteeing the right to the truth for victims and their families, and so forth (Id.).

Bosnia and Herzegovina is a difficult case that requires considerations of context-specifics to avoid harmful consequences. Therefore, education reforms should be based on ideology rather than on ethnicity and religion (Raynolds, 2017). The state authorities and governmental bodies should adopt policies in education, culture and the media—at all administrative levels—and provide comprehensive and accurate accounts on past violations based on established facts through international and domestic courts and narratives of victimhood, including educating people on history, culture and contribution to society of other ethnicities and nationalities (UNGA, 2022). The education policy reforms must entail: ending national or ethnic segregation, implementing a common core curriculum, including on history and geography, ensuring minority students’ access to learning on their mother language and cultural heritage, adopting a multi-perspective approach to history teaching, and preventing the intrusion of divisive ethno-nationalist agendas in school curricula (Id.). An inclusive, pluralistic approach to history learning implies the use of textbooks that, according to historians, explain events from both sides—not denying the siege of Sarajevo, but not neglecting the suffering of all residents, including Serbs, in the besieged city. Teaching methods, on the other hand, should encourage critical thinking, dialogue, questioning, and openness toward alternative versions of history (Davies, 2017; Wansink et al., 2025). In a broader context, Bosnia and Herzegovina should adopt a comprehensive transitional justice strategy, including a national truth-seeking commission, and integrate history education into transitional justice programs. A dialogue among institutional authorities, political leaders across all spectrum and ethnic, national and religious groups is necessary to harmonize education curricula and ending school segregation and discrimination. Once and for all (OSCE, 2020).

Literature:

Avramović, I. (2017). Reconciliation in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The NewBeyond Intractability.

BIRN Sarajevo. (2020, October 30). Bosnian, Serbian Schoolbooks Teach Rival Versions of History. By M. Obrenović.

BIRN Sarajevo. (2025, January 24). Bosnian Constitutional Court Bans History Lessons Glorifying War Criminals. By L. Memčić.

Cole, E. A. (2017). No Legacy for Transitional Justice Efforts Without Education: Education as an Outreach Partner for Transitional Justice. International Center for Transitional Justice.

Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina. (1995). Office of the High Representative, Department for Legal Affairs.

European Commission against Racism and Intolerance. (2024). ECRI report on Bosnia and Herzegovina. Council of Europe.

Fiedler, C., & Mross, K. (2023). Dealing with the Past for a Peaceful Future? Analyzing the Effect of Transitional Justice Instruments on Trust in Post-conflict Societies. International Journal of Transitional Justice, 17(2), 303–321. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijtj/ijad010.

Fischer, A. (2005). Integration or Segregation? Reforming the Education Sector. Berghof Foundation.

Forić Plasto, M. (2020). A Divided Past for a Divided Future!? The 1992–1995 War in Current History Textbooks in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Journal of the Faculty of Philosophy in Sarajevo, 295–314. https://doi.org/10.46352/23036974.2020.2.295.

Framework Law on Primary and Secondary Education in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Official Gazette of BiH, No. 18/03 (2003).

Gačanica, L. (n.d.). Is Reconciliation a Priority for Bosnia and Herzegovina? Initiative for Monitoring the European Integration of Bosnia and Herzegovina. https://eu-monitoring.ba.

George, E. (2007). After Atrocity Examples from Africa: The Right to Education and the Role of Law in Restoration, Recovery, and Accountability. Boston University School of Law Working Paper Series.

Human Rights Council. (2012a). Resolution A/HRC/RES/21/7: Promotion and Protection of all Human Rights. United Nations General Assembly. (2012b). Resolution A/HRC/RES/21/15: Promotion and Protection of all Human Rights. United Nations General Assembly.

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Dec. 16, 1966, 993 U.N.T.S. 3.

International Organization for Migration. (n.d.). Bosnia and Herzegovina Resilience Initiative.

International Center for Transitional Justice, & UNICEF. (2015). Education and Transitional Justice: Opportunities and Challenges for Peacebuilding (C. Ramírez-Barat & R. Duthie, Eds.).

Kovač, V. B. (2024). “Us” vs. “Them”: A Systematic Analysis of History Textbooks in Post-war Bosnia and Herzegovina Across Three Ethnic Educational Programmes. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 56(3), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2024.2436353.

Marshall Legal Institute. (n.d.). Inter-ethnic reconciliation program.

Mendeloff, D. (2004). Truth-seeking, Truth-telling, and Post-conflict Peacebuilding: Curb the Enthusiasm? International Studies Review, 6(3), 355–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-9488.2004.00421.x.

Moore, S. (2022, April 21). Bosnia’s Memory Problem: Competing Historical Narratives and the Threat to Peace. SLOVO Journal, University College London.

Ngobeni, R., et al. (2023). Curriculum Transformations in South Africa: Some Discomforting Truths on Interminable Poverty and Inequalities in Schools and Society. Frontiers in Education. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.xxxxxx (add article DOI if available)

OSCE. (2018). “Two Schools Under One Roof”: The Most Visible Example of Discrimination in Education in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Reynolds, A. (2017). Education Structure and Policy as Barriers to Transitional Justice in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Global Affairs Review, New York University.

Rethinking Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Past and Future: History Education Before the Constitutional Court. (2025, July 22). ICONnect. Soldo, A., et al. (2017).

Education in Bosnia and Herzegovina: What Do We (Not) Teach Children? Content Analysis of Textbooks of the National Group of Subjects in Primary Schools. Open Society Fund Bosnia and Herzegovina & proMENTE Social Research.

UN Economic and Social Council. (2005). Impunity: Updated set of principles to protect and promote human rights through action to combat impunity (E/CN.4/2005/102/Add.1).

UN General Assembly. (2005). Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, G.A. Res. 217A (III), U.N. Doc. A/810 (1948).

Leave a comment